It bothers him every time he sees one. It’s just too wide. He could have easily made the air intake 50 millimeters narrower. It doesn’t look right.

Luckily, you rarely see one—almost never on the road. We’re talking about the McLaren F1, and its creator, Gordon Murray. Every time he thinks about it, he cringes at the mistakes he made.

Though calling them mistakes isn’t quite fair. Back then, things just couldn’t be done any better. Materials weren’t what they are now, manufacturing methods were primitive, and computational tools were still limited. But the story behind it goes a little differently.

Imagine you’ve built the best car in the world. After two decades in the industry, crowned with Formula 1 world championships and the finest race car designs ever created, you produce that car.

Everything before it feels almost trivial. There were the wild, fire-spitting Ferraris—the 288 GTO and F40, which were as uncomfortable as they were unfathomable to drive. The bloated, over-engineered Porsche 959. The underwhelming Jaguar XJ220. And the overly ambitious Bugatti EB110.

Then came the McLaren F1—the purest form of the automobile.

Now, imagine the same thing happening again, 30 years later.

Everything since has been laughable. The bloated Ferraris. The heavy Porsche 918. The exaggerated McLarens, Pagani, and Koenigseggs. And yet again, Bugatti has overreached with ambition.

The new car is pure again.

The new car is the Gordon Murray Automotive T.50.

We once said that designing a car today, single-handedly, was impossible. We were wrong—though that’s not entirely true. So, what makes the T.50 so special? Two things: the vision of its creator and the name attached to it.

Gordon Murray has always been the best. A maverick—not just in his style. His race cars are all legendary, but none surpass the F1. Prices for the 72 road versions of the McLaren F1 are astronomical. Ten million euros for an average example, with the more special versions like the LM or Longtail going for double that. But it’s not just about flexing wealth—the McLaren F1 is simply irreplaceable. No car from the past 30 years has even come close.

It looks stunning. It sounds stunning. It drives stunningly.

Anyone with even a slight love of cars feels it when they see a McLaren F1. Everything about it is purely designed for driving—not racing, but driving. Sure, the F1 won Le Mans more or less straight out of the box, but that win was more of a bonus. The F1 was the best driver’s car—and its ease of use made it even faster than most race cars over long distances.

This is also why the modern supercar trinity—the hybrid Ferrari LaFerrari, Porsche 918, and McLaren P1—can’t evoke the same emotion as the F1. On paper, they beat the F1. In straight lines and around corners, they are faster. But they don’t deliver the sheer joy, the emotional depth, that the F1 did—and still does. Not even close.

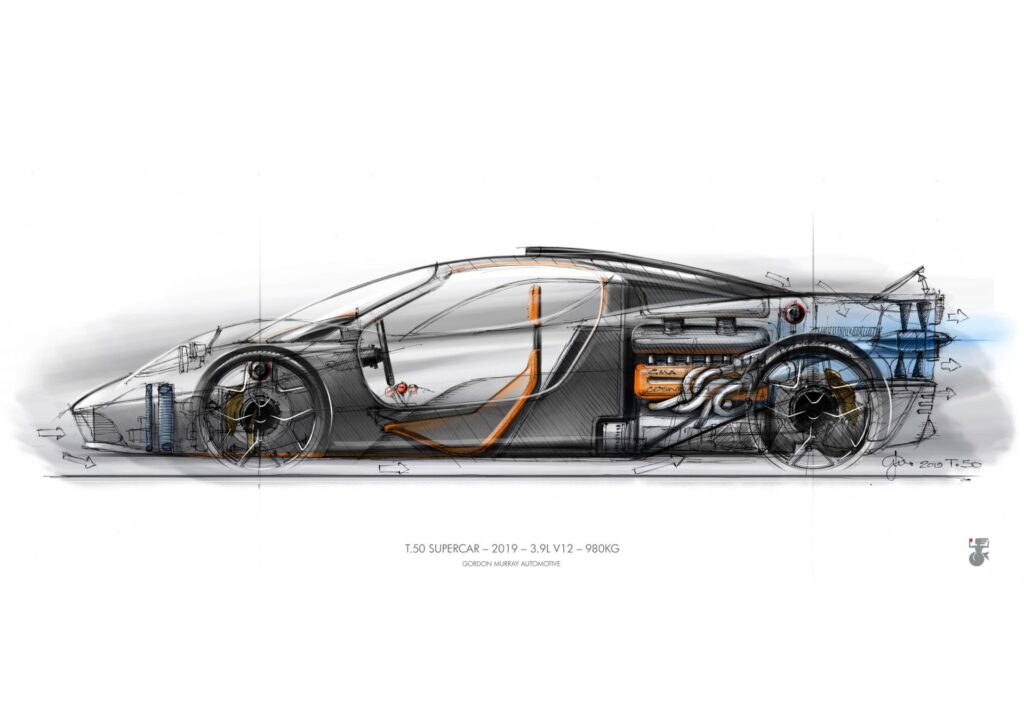

And that brings us to the T.50. Its vision is clear: remake the McLaren F1. Not with nostalgia or retro design, but with every bit of experience and technological advancement from the past 30 years—every lesson learned, every material improvement, every fabrication breakthrough.

The Chassis

Full carbon-fiber, of course. Murray has been working with carbon for over 40 years, so that’s a given. But this isn’t just any carbon-fiber—it’s a honeycomb construction, with high-strength aluminum inserts forming the core. The result? A chassis so tough you could drive a tank over it and still use it afterward. And it’s light. Incredibly light. The whole chassis, with all bodywork included, weighs less than 150 kilograms. That’s nearly half the weight of the McLaren F1’s chassis, a testament to just how far technology has come.

Aerodynamics were also a focus. Notice how the front wheel arches are tucked in? This wasn’t possible on the McLaren F1 due to limitations in carbon-fiber analysis and construction at the time. But with modern tools, Murray could achieve this, significantly reducing drag and allowing for better airflow venting from the wheel wells and radiators. This, Murray says, accounts for about 30% of the car’s overall aerodynamic efficiency.

The Engine

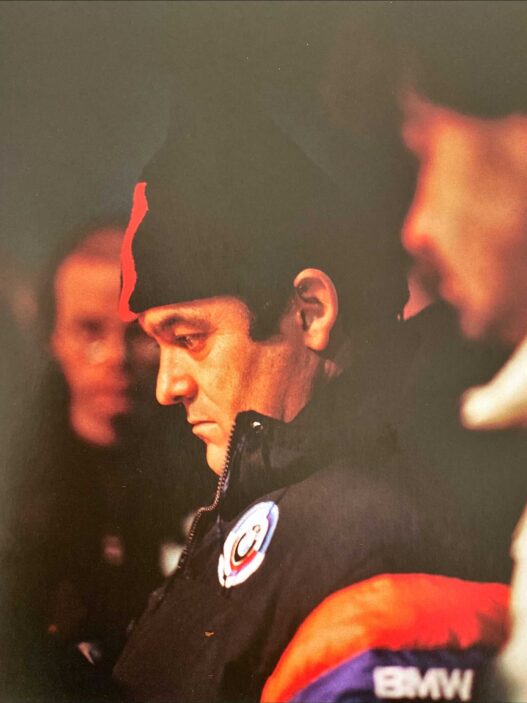

When designing the F1, Murray initially sought to partner with Honda, but the task was too much for the Japanese automaker. They couldn’t deliver a V12 engine that met Murray’s stringent weight and power requirements. That’s when Murray called Paul Rosche at BMW, and the rest is history. Rosche not only delivered the engine for the McLaren F1, he exceeded the power target by 77 horsepower—giving the F1 a total of 627 hp.

Fast forward to the T.50, and Murray wanted to repeat the magic. The number of cylinders was non-negotiable: twelve. Anything less wouldn’t deliver the refinement Murray sought, and anything more would just add unnecessary weight. The displacement, however, took some back-and-forth. Initially, Murray wanted 3.3 liters, a nod to the iconic Colombo V12 from Ferrari, but after calculations and testing, they settled on 3.9 liters.

This engine, developed by Cosworth, isn’t just powerful—it’s alive. The T.50’s 3.9-liter V12 revs so fast it will take your breath away. The engine hits 8,000 RPM in the blink of an eye—literally. It revs faster than any road car engine before it. The numbers are just as jaw-dropping: 663 horsepower at 11,500 RPM, 467 Nm of torque at 9,000 RPM, and a redline at a staggering 12,100 RPM.

And the sound—it’s glorious. Murray has always said that 50% of the driving experience comes from the engine’s sound, and he ensured the T.50 delivers. The roof-mounted air intake doesn’t just feed the engine air; it amplifies the intake sound and funnels it directly into the cockpit, giving the driver an immersive experience like no other.

The Transmission

Initially, Murray considered a sequential gearbox for the T.50, but his customers had other ideas—they wanted a manual. So, Murray obliged. Xtrac developed a six-speed manual specifically for the T.50. This gearbox is a mechanical masterpiece, with lightweight titanium internals and precise gear ratios designed for the ultimate driving experience.

But Murray wasn’t satisfied with just a great gearbox. He wanted perfection. The shift lever, made from titanium, was initially too thin, bending under load during testing. Murray had it thickened by a mere 1mm, solving the issue while maintaining the lightweight, responsive feel he demanded.

The Aerodynamics

Murray’s love for aerodynamics is evident throughout the T.50’s design. At the rear of the car, a 40cm turbine fan extracts air from the underbody, creating massive downforce while reducing drag. This fan, a nod to Murray’s Brabham BT46B Formula 1 car from the 1970s, isn’t just a gimmick—it works. In Vmax-Boost mode, the fan generates an additional 15 kilograms of downforce, pushing the T.50’s power output beyond 700 horsepower.

But the fan isn’t always about downforce. In “Streamline” mode, the T.50 reduces drag by redirecting airflow, effectively turning the car into a virtual longtail, reducing the wake behind the car and allowing for higher top speeds.

The Comfort

Despite being a no-compromise driver’s car, the T.50 is surprisingly comfortable. There are no touchscreens to distract the driver—everything is focused on the driving experience. The steering wheel, shift lever, and pedals are all positioned perfectly for the driver, who sits in the center of the cockpit, flanked by two passenger seats.

Murray didn’t just focus on performance, though. He ensured the T.50 would also be an enjoyable place to spend time. The sound system, developed by British audio company Arcam, features 10 speakers and 700 watts of power, all while weighing just 3.9 kilograms. The climate control system, powered by the car’s 48V system, ensures the cabin stays cool even in stop-and-go traffic—a problem the McLaren F1 struggled with.

The Verdict

The T.50 is a masterclass in automotive design. Every detail has been meticulously engineered for one purpose: to be the best driver’s car in the world. And it succeeds. Weighing just 986 kilograms, with a naturally aspirated V12 and a manual gearbox, the T.50 is the purest form of driving joy. Only 100 will be built, priced at 2.36 million pounds each—and they’re likely all already spoken for.

Gordon Murray has done it again.